by P.N. Zoytlow, Occasional Lecturer

Including a brief discussion of Hyperbolic Americana

I am a minor deltiologist, which means I collect postcards, though my zeal is sporadic. I am signaling you not to expect expertise. Deltiology is a word derived from the Greek for “writing tablet.” But who collects writing tablets? So, the name is reserved for those familiar small stiff cards with images and messages, usually cheery.

These days, collected postcards are found in antique shops, which also offer collectibles, which is what postcards are. The collector is most keen on the vintage postcards, but where does “vintage” begin and end? That’s subjective. Sometimes, it’s the physical nature of the card itself, meaning the quality of the color or photograph. For my purpose here, I assigned the period ending around 1950 to the vintage era. Certain topical postcards dominate other decades, such as the tall-tale cards, which are the main focus of this presentation. It’s usually the look, feel, and context of the vintage card that the deltiologist decides finds attractive. Only some postcards offer the date of publication. However, there are other sources of information for dating details of the photo (the year a vehicle was made, years of operation of a hotel, and production style ( is it a “linen” card?). A card with a message on the back may be dated.

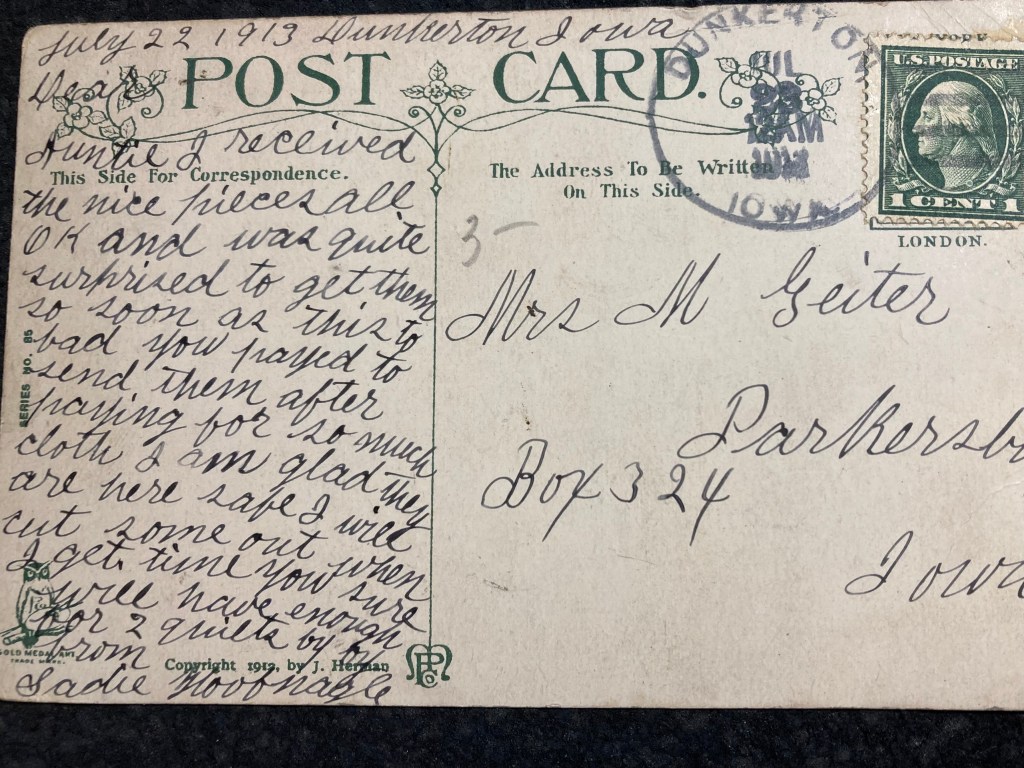

A word about messages: these are usually quite banal, along the lines of “wish you were here” or “home on Monday” and so on. However, some can be charming and glimpse a bygone time. Consider this one on the message side of one of the giant vegetable cards shown below. Dated July 22, 1913, and posted at Dunkerton, Iowa, Mrs. M. Geiter of Parkersburg, Iowa, gets a message about quilting materials from her niece, Sadie Hoofnagle.

An earlier and far- less polished card is the following. It is a view of the Santa Fe, New Mexico plaza, 1908. The publisher, J.S. Candelario, also sold “Wholesale and Retail Indian Goods” and offered (for 2 cents) to send a price list and a “Souvenir to Ladies.”

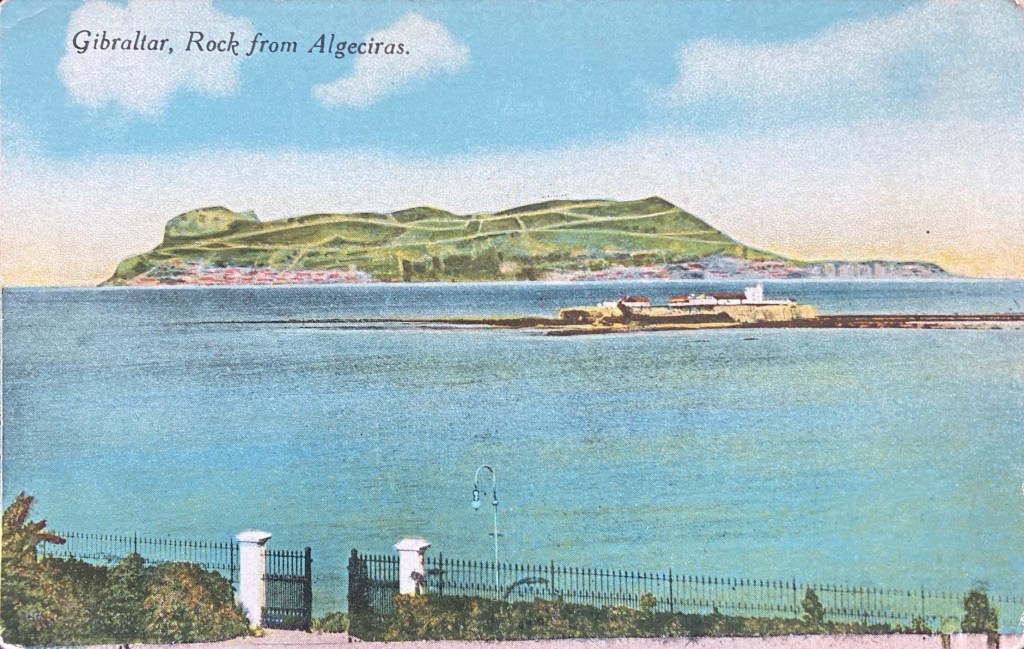

A more typical vintage card features a view of a place; buildings and landscapes are standard. A different view of Gibraltar is shown in this card, which was printed in Scotland. Due to the popularity of postcards in the days before widespread or cheap telecommunications, there were many producers. And remember, they cost one cent to send domestically.

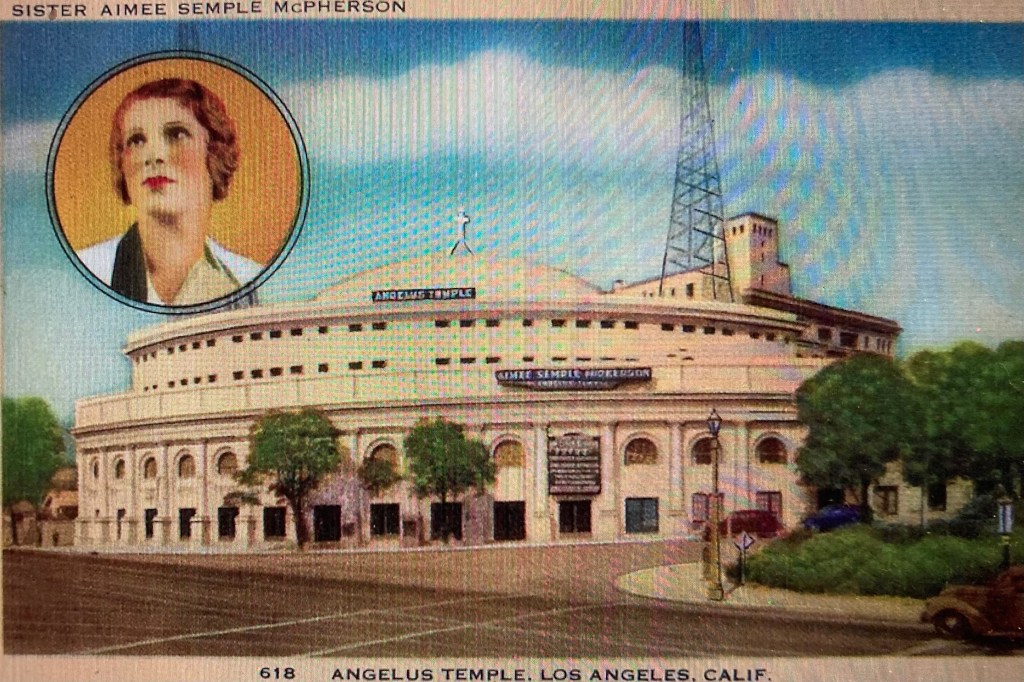

Aimee Semple McPherson was a prominent evangelist in Los Angeles beginning in the 1920s. The temple was built in 1923. This card is probably later, judging by the model of the automobile on the lower right. Sister Aimee attracted an enormous following as well as some headline-grabbing scandals.

One qualifies as a vintage card because the days of Northwest Airlines and the Stratocrouser are over. This airlinerhad many “luxury features [to] distinguish these modern giants of the skies.” They were common in the 1950s but became obsolete with theadvent of jet travel by 1960. Northwest was absorbed by Delta Airline

Many vintage cards seem naive, perhaps even stupid, by today’s expectations. These may cause today’s viewer to shrug and think, “So what.” Often, these feature underwhelming details of local parks, a modest fountain, or simply an avenue. It’s doubtful they are designed to impress the folks back home. The example here is from Winona Lake, Indiana.

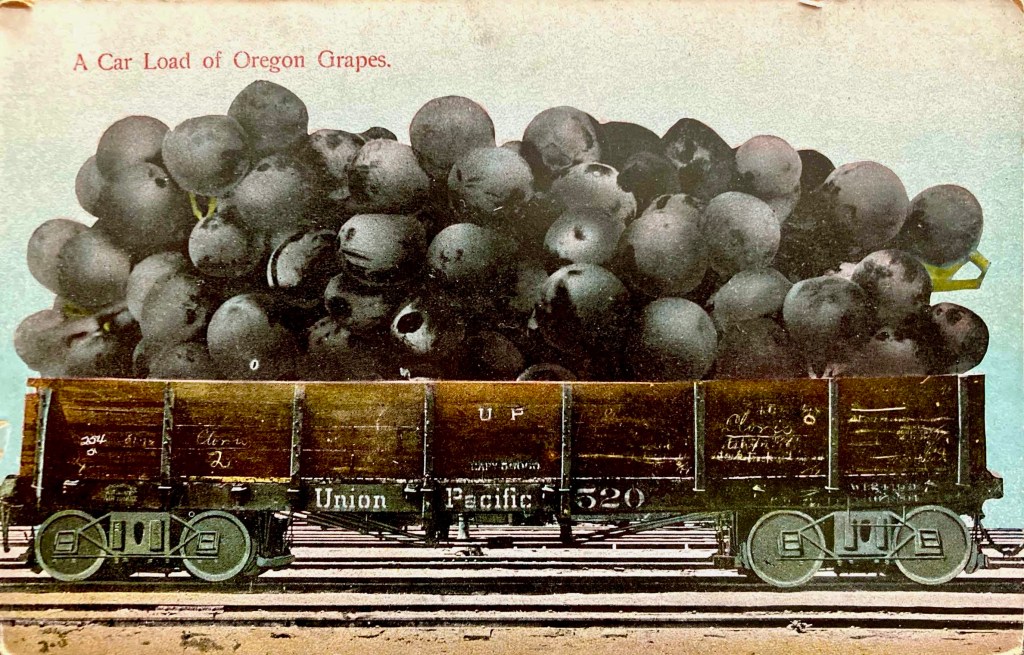

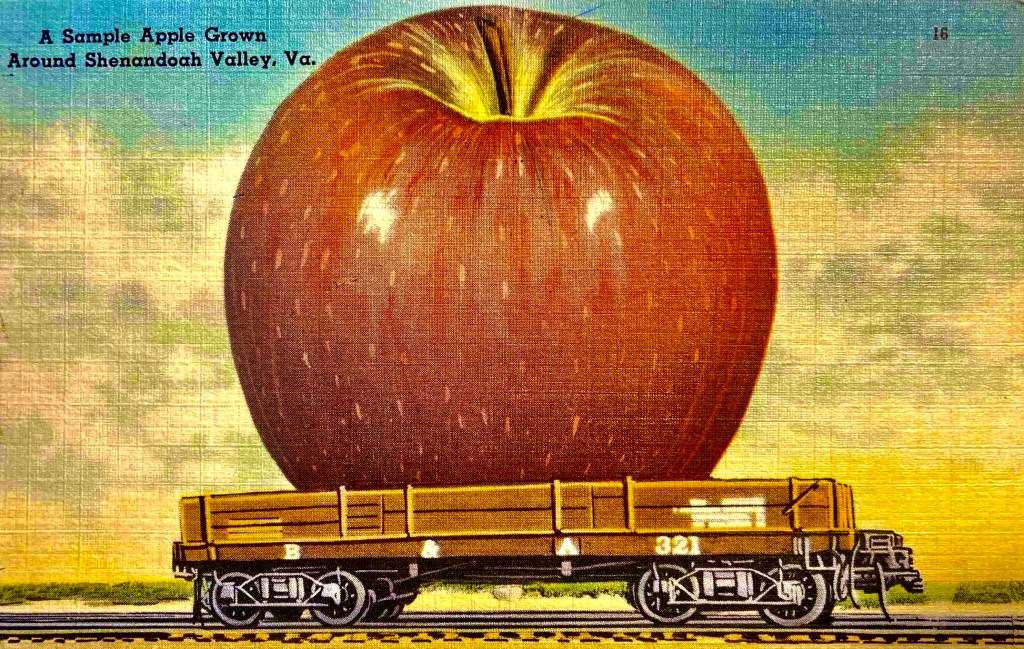

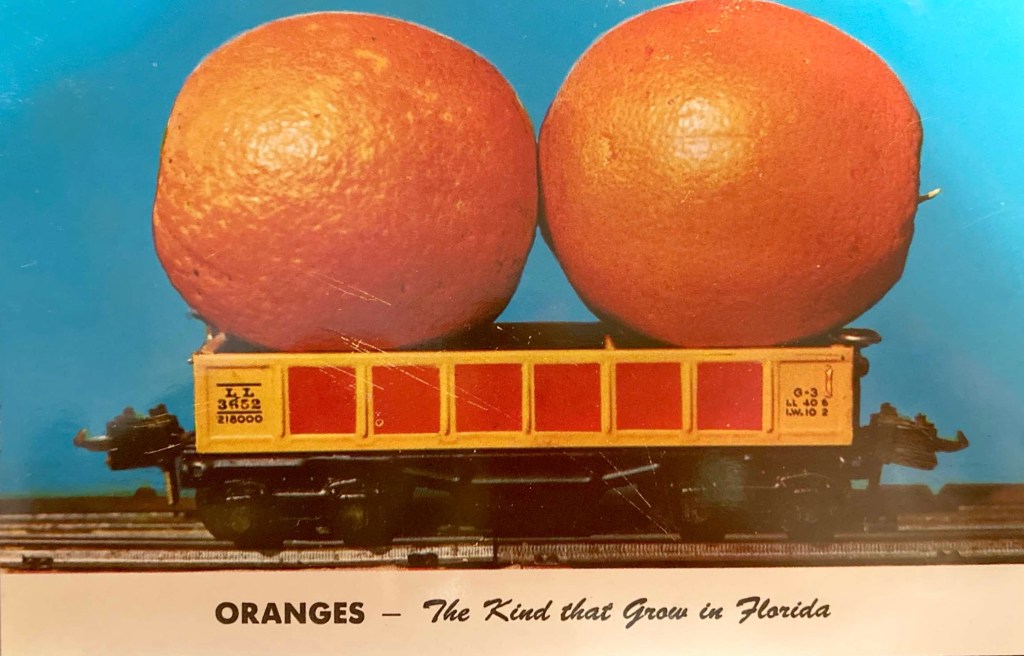

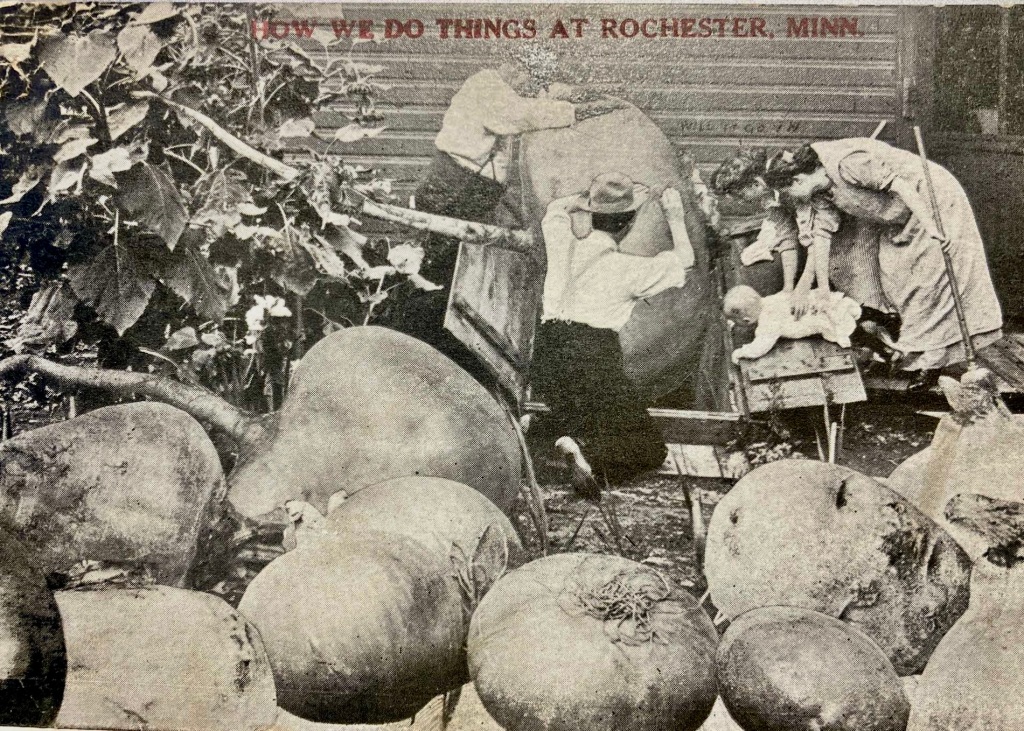

That small introduction to vintage postcards aside, this deltiologist now shares with you the focus of his past and occasional collecting: the rural exaggeration card. Also known as the tall tale card or simply the whopper. These cards were trendy in the first half of the 20th Century. Several observations may point us in the direction of explaining the phenomenon.

- Large, champion agricultural products have always drawn people’s interest, so state or county fair visit1ors are attracted to giant prize-winning pumpkins, apples, and watermelons. Of course, large farm animals will also draw crowds.

2. The need for the agricultural sector to draw competing attention to itself as urban growth exploded and skyscrapers began to command more attention and became the iconic symbol of a powerful, advanced nation.

3. Newer methods of producing postcards coupled with advances in darkroom technology meant a widespread availability of an increasing number and variety of cards.

4. A trend took root, and local boosterism and increased tourism fed a craze for whopper cards. Rail and automobile travel allowed penetration of rural areas and the desire to use postcards to advertise mobility.

5. American exceptionalism is apparent in many forms of expression, but all were based on the conviction that there was something special and superior about the United States. Pride in democracy, the size of the nation, or a particular feature such as Niagara Falls were the mainstays of this exceptionalism. Now, a gigantic potato might serve the same purpose.

6. Related to this was the need to embellish the myth of the promised land, an Edenic continent, to contrast itself to exhausted Europe. This notion can be traced to earlier arrogant views of some European philosophers that Americans and their efforts were always puny. Buffon and de Pauw argued against the exceptionalism of nature in America, but most of their arguments were directed against the fauna, not the flora.

As a minor deltiologist, I would be thrilled to state unequivocably that Americans during the first three decades of the 20th Century promoted tall-tale postcards to rebuff some arrogant Europeans in the 18th Century, but that’s just not so. Those insulting views had long been put to rest. [Interesting sidebar here: Jefferson sent Buffon a giant specimen of a moose, which, we are told, helped nudge that philosopher towards recanting his earlier theory.]

Of course, I should have been suspicious that none of the writers on the subject of postcards, some quite scholarly, connected Buffon and, say, a giant melon on a railcar. Nevertheless, who among us would be able to resist presenting such a bombshell paper at a distinguished academic conference?

Enough, let’s look at some postcards.

The particualar state was not identified pointing out how generic these cards became. Often the same flatcar was used to carry the giganitic fruit or vegetable.

What is happening to that baby?!